By Audley specialist Iain

The thing you have to be prepared for in Chile is the open space: the Patagonian ice fields and the arid altiplanos of the Atacama Desert. Yet within such emptiness, there’s much to see. The desolate red rock plateaus of the Valley of the Moon. The Grey Glacier’s immense, saw-toothed snout. A lake of icebergs the size of houses.

Chile is a place of environmental extremes geographically isolated from the rest of South America. But this isn’t its only draw. I have a soft spot for the rainbow-hued, graffiti-blazoned coastal town of Valparaíso. Elsewhere, in the Lake District, you can venture out to Chiloé Island. Not as far-flung as Easter Island, it’s still a world apart from the mainland.

Flying is unavoidable when journeying around Chile, but some regions are more suitable for self-driving. I’ve gathered together in this guide the areas I’d recommend exploring.

Explore Torres del Paine National Park, Patagonia

Getting to Chilean Patagonia is a journey to the end of the earth. It involves a three and a half hour flight from Santiago to Punta Arenas, then a five- or six-hour drive to Torres del Paine National Park.

A wilderness of scrubland, ridges, rivers, lakes and lagoons, the highlight is the eponymous torres (towers) of the Paine Massif. Out of the grasslands of the Patagonian Steppe, with its herds of grazing guanacos (which are akin to llamas), soar the 2,800 m (9,186 ft) high gray granite monoliths. They form part of the tapering spine of the Andes.

You can experience the park in many different ways, such as hiking, boat trips across glacial lakes, and horse riding. The last activity was particularly fun. I liked meeting our guides at their ranch, and learning about the gaucho culture that’s so rooted in Patagonian tradition. There was something romantic about journeying across this wilderness on horseback, the massif looming in the background.

- For recommendations on how to experience Torres del Paine, read our guide to Patagonia

Geological phenomena of the Atacama Desert

Moving to northern Chile, a two-hour flight from Santiago brings you to the Atacama Desert. It’s one of the most austere, driest places on Earth, a high-altitude 1,200 km (745 mile) expanse of dunes, plains, peaks, and active volcanoes.

It’s almost entirely devoid of plant life. The only vegetation is cacti and the occasional hardy flower like the bromeliad. Salt pans, altiplanic lagoons, geyser fields and valleys of lunar-like rock formations break up the desert plains. There are also several astronomic observatories — the Atacama’s altitude and cloud-free skies make for superb stargazing conditions.

In such an unforgiving terrain, human settlements are few and far between. The only one of any significance is San Pedro de Atacama, an oasis town. Squat adobe buildings line interlocking cobbled streets haunted by stray dogs. But even if it may seem like a dusty pioneer outpost at first glance, it’s full of elegant hotels and good restaurants. Overall, it makes a great base for making short trips into the surrounding desert.

Aim to see sunset at the Valley of the Moon, a 90-minute drive from San Pedro de Atacama. Here, take a short walk to a lookout on a dune hanging over the valley. As the sun goes down, watch how the wind-whipped rocky outcrops change from brown to red, orange, gold and pink.

A visit to El Tatio geysers, a field of steaming fumaroles, requires a 4am start and plenty of warm layers, as night sees sub-zero temperatures.

I arrived bleary-eyed at 6am. The water in the fissures began to bubble, then the cracks emitted clouds of steam. As soon as a geyser erupted, everyone in my small group rushed over. We admired the spectacle of the water spurting skywards, and basked in the heat it gave off.

A short drive from San Pedro de Atacama lie the San Pedro salt flats. Other than a small booth where you buy tickets, the shimmering flats sit in a vast basin with no sign of human presence. A line of volcanoes towers over the salt pans on one side. The salt is jagged and uneven, and crunches underfoot.

I made my way along the marked path that weaved through the flats. Suddenly, it brought me out at a crystalline lagoon full of pink flamingos busily feeding on algae. This apparently empty, hostile environment can also bloom with life.

Visit Easter Island

A five-hour flight from Santiago out into the Pacific, you’ll think you’re leaving Chile behind. And you are. Easter Island feels more Polynesian than Latin American.

The island’s monolithic sculpted stone statues (moai) are what you’re here to see and they don’t disappoint. There are no ropes or fences — you get right up alongside these colossal faces.

A guide will explain the complicated, tragic history of the island’s aboriginal people, the Rapa Nui, and the theories behind the statues’ existence. There’s also the chance to explore other, lesser-known sites around the island.

Get to know Chile’s cities

Wander around bohemian ³Õ²¹±ô±è²¹°ù²¹Ã²õ´Ç

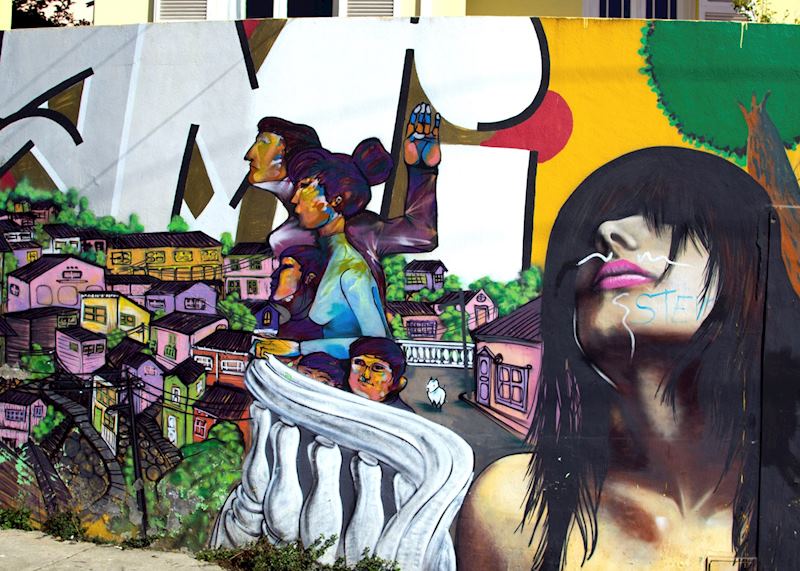

Pretty would be the wrong word to describe this city, a one and a half hour drive from Santiago. A working port that was once a trade hub, ³Õ²¹±ô±è²¹°ù²¹Ã²õ´Ç is a sprawl of brightly painted buildings spilling down hillsides toward the ocean. Many have corrugated iron façades, giving the whole city a raw, rough-and-ready look.

³Õ²¹±ô±è²¹°ù²¹Ã²õ´Ç’s economic fortunes suffered after the building of the Panama Canal. But the tide is turning. Several boutique hotels and stylish restaurants have sprouted among its boulevards and steep streets. On New Year’s Eve, it hosts one of the biggest firework displays in South America.

This jubilantly shambolic city won my heart when I took a trip on its funicular railways. Cramming into a rickety carriage only big enough to hold a handful of people, you’re carried up the city’s hills. From the top, there are sweeping views over the city and the bay.

Internationally acclaimed Chilean poet Pablo Neruda was a resident of ³Õ²¹±ô±è²¹°ù²¹Ã²õ´Ç. His former home, La Sebastiana, has some of the city’s best vistas and is now open to the public. Shaped like the hull of a ship, inside it’s a treasure trove of eccentric trinkets and decor reflecting Neruda’s love of the sea. Fake parrots, ships in glass bottles, tillers and a busty figurehead are on display.

Possibly the best view in all ³Õ²¹±ô±è²¹°ù²¹Ã²õ´Ç is from the poet’s desk, which looks out to the Pacific. He’s thought to have written many poems about the natural world seated in this spot.

Funicular-hopping aside, the best way to see ³Õ²¹±ô±è²¹°ù²¹Ã²õ´Ç (known as ‘Valpo’ by local people) is to wander at will. Keep your eyes peeled for the graffiti and street art that jumps out at you from all angles. A huge mural of a cat, its body arched around a building’s window, particularly sticks in my mind.

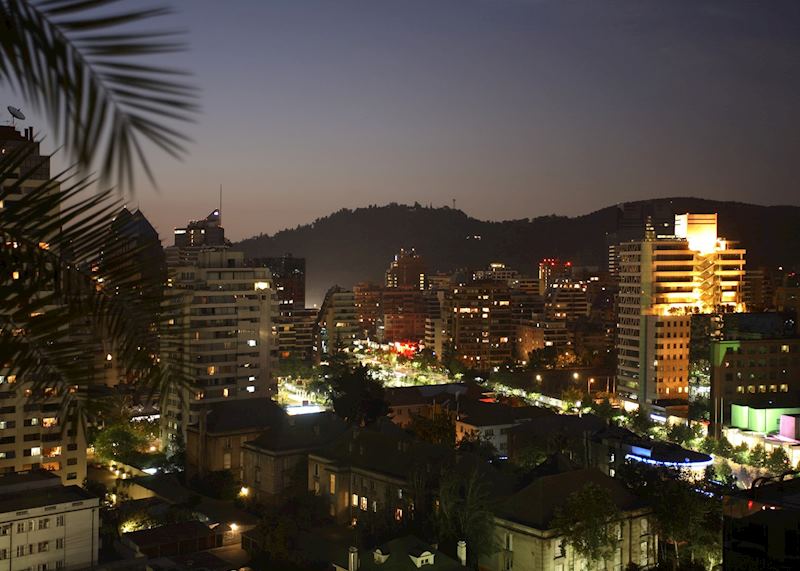

Admire the views from San Cristóbal Hill in Santiago

All roads (and flights) lead to Santiago, even if Chile’s capital doesn’t always receive very good press.

A mixture of skyscrapers and colonial architecture, it can sometimes feel a little business-like. It certainly stood out to me as less Latin than other nearby South American capitals, perhaps lacking the zest and bite that makes cities like Buenos Aires so intoxicating. However, I’d say it’s worth spending a couple of days here, if only to see the city from the top of Cerro San Cristóbal.

Located in the northern reaches of the city, this hill houses a park, zoo, playground and botanical garden. First-time visitors should head straight for the Terraza Bellavista viewpoint. Here, you’ll get a panoramic view of the modern high rises, with the snow-capped Andes as a backdrop. Take the cable car back down — or the steep dirt path if you’re feeling fit.

Get behind the wheel in the Lake District

This region is often described as a gentle introduction to the wilder landscapes of Patagonia and the Torres del Paine. And yet, with pristine forests, cobalt-blue waterfalls, and lakes scattered from Pucón (a one and a half hour flight from Santiago) to Puerto Varas, the scenery is hardly insipid. Where else would your lakeside hotel room overlook an active volcano, its cone sheathed in snow?

You can circumnavigate this volcano — named Villarrica — on a hike. Fishing, cycling and horse riding are also popular throughout the region.

The great thing about the Lake District is that it can be a hive of activity or a place to unwind. Take your time exploring some of the smaller, less visited lakes like Puyehue or Tagua Tagua by hire car. Roads in the region are well-maintained, making self-driving easy.

Explore °ä³ó¾±±ô´Çé Island

Part of an archipelago in Chile’s southern Lake District, you reach the main island of °ä³ó¾±±ô´Çé via a short ferry ride from the mainland. The boarding point is about an hour’s drive south of Puerto Montt airport. Partially uninhabited and half-hidden in a tangle of wild forest, °ä³ó¾±±ô´Çé can also be explored by car. You can travel the length of the main island, on tarmac roads, in three hours.

°ä³ó¾±±ô´Çé and its outlying islets are dotted with 200 ornately designed wooden churches originally built by Spanish occupiers. Sixteen are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. On the shores, and especially in Castro, °ä³ó¾±±ô´Çé’s main town, you’ll see palafitos, overwater bungalows on stilts. They’re painted in a palette of orange, turquoise, red and yellow.

Wandering around the squares and streets of this laid-back town, you’ll catch the scent of the local dish, curanto. Seafood, meat and potatoes are layered and covered in the leaves of locally grown wild rhubarb, then left to cook over hot stones. You may also hear the sounds of °ä³ó¾±±ô´Çé’s traditional music. You’ll know it by the sound of the accordion, a legacy of the island’s German settlers. It’s fused with traditional Spanish and indigenous sounds.

Unlock Chiloé's history and culture with a local guide

It’s not just the cuisine, music and the architectural idiosyncrasies that give this island its distinctive personality. A guide is essential to help you access the island’s rich history and folklore.

From my guide, I learned that the Spanish, having conquered most of the mainland, arrived on °ä³ó¾±±ô´Çé in a more conciliatory mood. The indigenous people, the Mapuche, converted to Catholicism and struck up a friendship with them. In fact, °ä³ó¾±±ô´Çé still refers to itself in a tongue-in-cheek manner as a ‘republic’. When Chile declared its independence, °ä³ó¾±±ô´Çé wanted to remain Spanish.

Try, if you can, to visit a couple of the wooden churches. They’re in surprisingly good condition despite their warped columns. An excellent museum in Ancud, in the northern part of the island, explains their origins. I learned how, in the absence of masons, the Spanish used the skills of local boat builders to construct these places of worship. As a result, many churches resemble upside-down boats.

One day, my guide took me on a walk around the western side of the island. I was tickled by the legend of the sylvan troll Trauco. In the context of Chile’s strongly Catholic society, he’s blamed for unmarried women falling pregnant.

We then came to a beach where a wooden walkway led out over the ocean, suspended in mid-air. It looked like a strange sort of unfinished pier. My guide whispered its name: the Bridge of Souls. According to Chilote mythology, you’ll walk it when you die.

Start planning your trip to Chile

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in Chile