By China specialist Anthony

Some of China’s most beguiling spiritual places aren’t museum pieces: they’re functioning places of worship hosting thriving communities. And, while modern, urban China can seem like a fiercely secular place, you can also observe first-hand how spirituality and religion plays a strong role in people’s lives. It’s a part of visiting China that never fails to fascinate.

I’ve selected sites — Buddhist, Daoist, even Islamic — that mostly take you out of the big cities, and often to places that few Western visitors reach. You can thread all of them into a classic 13- to 14-day China trip.

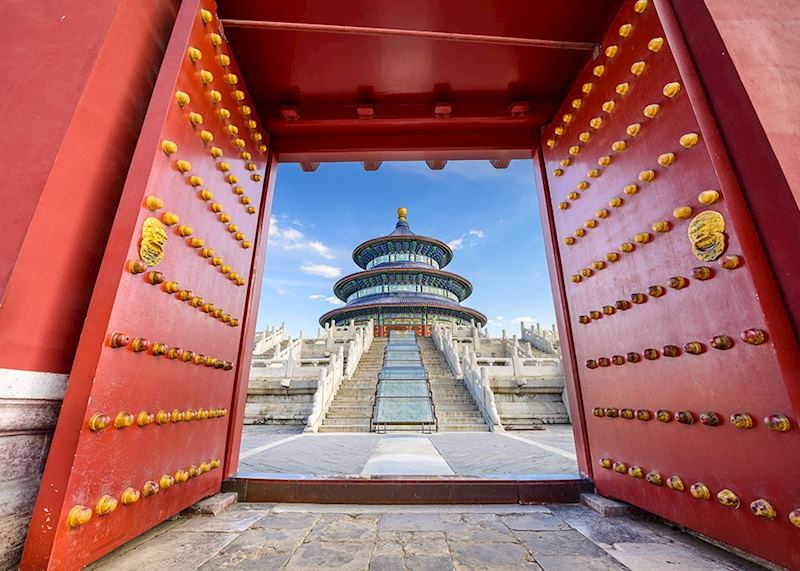

Temple of Heaven Park, Beijing

One of China’s most identifiable and eye-catching spiritual sites, this isn’t a single temple (despite the name), but a series of altars and prayer halls dating back to the 15th century. You can easily work a visit to this large complex to the southeast of Beijing into most trips, including your first time in China.

The Temple of Heaven is set among austere white-marble terraces, lovingly tended gardens, gnarled cypress trees, and pinewoods. Confucian design principles are at work here, too, in the complex’s regimental straight lines.

Make the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests — the complex’s showpiece — your first port of call. This triple-decker circular temple is wrapped in a rainbow riot of Ming and Qing friezes, while its indigo-blue roof tiles represent the firmament.

Peeking into its exuberantly kaleidoscopic interior (you can’t actually step inside) gives you a glimpse of where emperors once kneeled to beseech a higher power for a bountiful crop. Examine the hall’s structure and you’ll see that, like many wooden spiritual buildings in China, it has no nails.

Next, I’d head to the Circular Mound Altar, where emperors would pray for rain and sacrifice bulls at the solstices. Look closely and you’ll see how this immaculately preserved marble-and-bluestone altar revolves around the number nine (a number powerfully associated with imperial authority). Its steps, terracing and flagstones are all arranged in nonuples.

Acoustically, it also has some tricks up its sleeve. Stand and speak on the central stone, on the altar’s uppermost level, and you might notice how your voice is abnormally amplified.

Although the Temple of Heaven receives scores of visitors daily, it’s at its most serene early in the morning, when the gates open at 8am.

After your guided visit of the main buildings, I’d recommend taking a t’ai chi lesson in the Temple of Heaven’s grounds.

Even if you’re a curious novice, it can be satisfying to try this meditative art in the country of its birth, guided by a skilled practitioner. When I tried it, my teacher was an elderly lady who taught me basic movements in a shady corner of the complex one morning. If nothing else, it’s a good way to wind down after a couple of hours’ intense exploring.

Spiritual sites in Shanxi

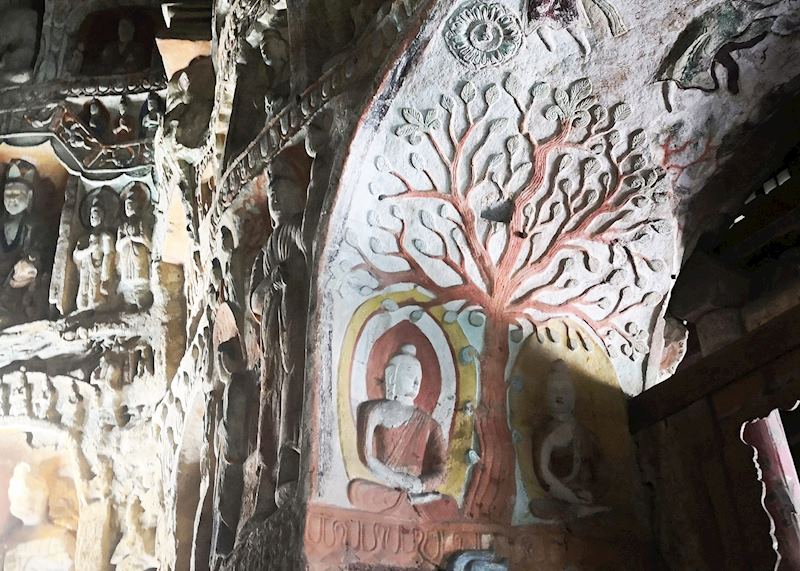

Yungang Grottoes, Datong

A seven-hour train journey or a half-hour flight from Beijing to Datong, followed by a 45-minute drive, deposits you at the foot of a towering sandstone cliffside. Here, in the 5th century, the Tuoba people gouged out a series of caves that they filled with Buddhist carvings. The statues and reliefs appear far more Indian or Persian than classically Chinese — a result of influences flowing along the Silk Route.

The image most associated with the site is that of an immense seated Buddha. It has survived, somehow, despite being exposed to the elements when its cave front collapsed.

But, for me, the real finds are in caves five, six, nine and ten (several caves are open to the public, so ask your guide to be choosy).

These caves in particular are almost overwhelming in the richness and detail of their carvings (they reminded me of Rococo or Churrigueresque church interiors). Much of the original paintwork remains vivid, and every surface is vigorously ornamented with Buddhas and a host of figures to guide you on your own journey to enlightenment.

At the other end of the scale, look out for a modest, half-finished Daoist grotto (abandoned due to funding shortfalls).

Hanging Monastery, Datong

A short drive from Datong, and as old as the Yungang Grottoes (though perhaps not as well known internationally), this peculiar wooden stilted temple is tucked into an overhang on the side of a gorge. The wooden stilts are, in fact, only there for show and provide no structural support.

You process through its series of suspended halls and cabinets on a one-way system. Inside, Buddhist, Confucianist and Daoist designs sit cheek by jowl, and (unusually for China) you’ll see statues of their three leaders grouped together.

Just around the corner from the tourist honeypot of the Hanging Temple (again, it pays to arrive early), stairs lead up a cliffside behind a small dairy farm. The steps culminate in a very small, modest Daoist temple, used exclusively by local devotees. I’d ask your guide if you can head up there, as long as you want to tackle the steep climb.

At the top, you’re rewarded with a view: the temple overlooks a vast plain. And, if you see them, don’t be afraid to stop and chat with the temple’s duo of dark-blue-robed priests.

Mount Wutai

Mountains are often seen as sacred in China because they’re close to the heavens, and they give life to rivers. Visiting one of China’s hallowed Buddhist mountains not only exposes you to some of the country’s finest scenery, but you might also witness displays of intense religious and spiritual devotion that you won’t see anywhere else.

Despite its name, Wutai (‘five peaks’) can be misleading. It’s really a cluster of 47 temples, surrounded by five flat-topped peaks swathed in evergreens and crowned with a temple each. The peaks’ positions correspond to Buddhism’s cardinal points.

Such a dense concentration of temples can leave you at a loss as to where to start, but I’ve found that guides are good at steering you to the most interesting specimens. Tayuan Temple is identifiable by its snow-white Ming stupa, while others are gilded or filled with prayer wheels.

Dailuoding Temple is, in my view, the most rewarding to visit. Before going, I’d always associated Buddhist temples with private devotions: you typically see people praying and lighting incense sticks as an offering before departing. But, Dailuoding was a hive of communal activity.

It’s at the top of a huge flight of stairs, which you can skip by taking a chairlift. But, on the stairway, you’ll see pilgrims taking just three steps before kowtowing, repeating the process until they reach the top. It takes them hours.

Then, inside the temple, you might see groups of gray-robed visiting Buddhists chanting mantras, or receiving lectures from their teachers.

‘Am I okay just watching?’ I asked my guide. I felt like I was intruding on many people’s deeply felt rituals. ‘Yes’, said my guide, and pointed to some clumps of domestic visitors standing around and watching the proceedings from the sidelines. ‘See? They’re intrigued just like you. This is new to them, too.’

Great Mosque, Xian

This is another site that slots easily into China itineraries, since you’ll likely visit Xian at some point if you wish to see its famed Terracotta Army. If you’re coming from Mount Wutai, you’ll probably get here by train, taking in the walled city of Pingyao (China’s former financial powerhouse) en route.

Many visitors to Xian venture into its Muslim Quarter’s night markets in search of aromatic street food. But, comparatively few return by day and set foot inside the mosque that’s the focal point for Xian’s Huà community.

In my book, the mosque makes for a really rewarding detour. You’ll experience a segment of China’s religious mosaic that isn’t Buddhism or Daoism, and observe its curious blending of Islamic art and classical Chinese architecture, in which its minaret appears to masquerade as a pagoda.

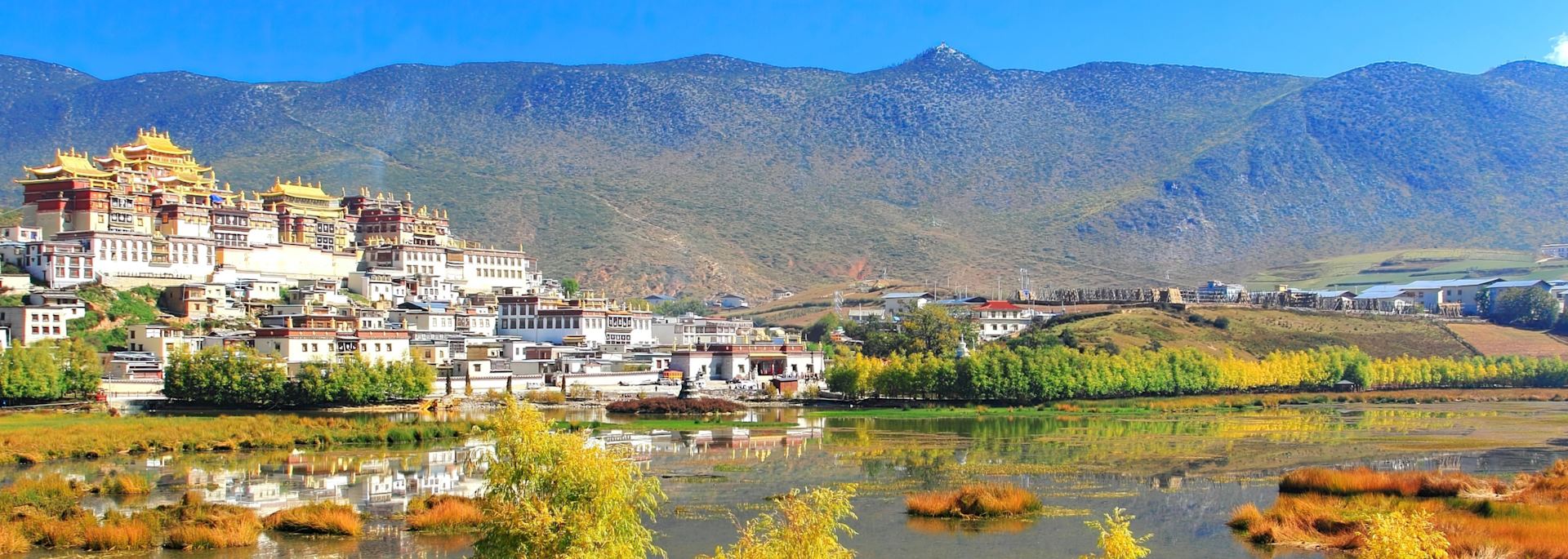

Songzanlin Monastery, Shangri-La, Yunnan

From Xian you can fly to Lijiang (which takes less than three hours), stopping for a few days in this mountain-shadowed town and adjusting to a slightly higher altitude before driving on to the frontier-like town of Shangri-La.

Located ten minutes’ drive from Shangri-La (which shrewdly remarketed itself as ‘Shangri-La’ on the back of the success of James Hilton’s Lost Horizon), Songzanlin is a palace-like edifice of watchtowers, gates, classrooms, prayer halls and courtyards, topped by spangling gold-plated roofs. If you’re interested in observing the workings of a Tibetan Buddhist lamasery (without going to Tibet), and experiencing one of China’s most rural and remote provinces, I’d highly recommend a visit.

Seven hundred monks live here today, and on a guided visit you can see them studying and going about their business. You’ll see monks of all ages, from as young as five.

The air feels icily clean, and, given you’re 3,300 m (10,826 ft) above sea level, you might find yourself gasping for breath as you walk to the monastery’s upper levels. The ascent is worthwhile: you’ll look over to Shangri-La shimmering in a valley, cupped by mountains whose tops are often clouded in snow.

Read more about trips to China

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in China