By China specialist Chris

‘We’ve broken a Buddha,’ cried the farmers who stumbled across a pottery torso and head as they were digging a well near Xian, northern China. The year was 1974, and little did they know what they’d unearthed: a life-size army of 8,000 warriors and horses built to accompany China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, in the afterlife. To date, only a fraction have been unearthed.

Today, the Terracotta Warriors rank high on many travel wish-lists. So, here’s my advice for how you can plan your visit in a way that will enhance your overall experience. And, don’t overlook Xian itself: there’s much more to China’s ancient capital than its archaeology.

Making the most of your visit to the Terracotta Army

A guide is essential for getting the most out of seeing the warriors. Not only will your guide go into detail about aspects that particularly interest you, but he or she will also point out elements that are little-known or not immediately apparent. Guides are also excellent at filling you in on the convoluted, soap-opera-like Qin dynasty politics.

The museum housing the warriors, located about an hour’s car ride from Xian, consists of three main ‘pits’ — vast underground chambers in which different sections of the army were discovered.

Pit One

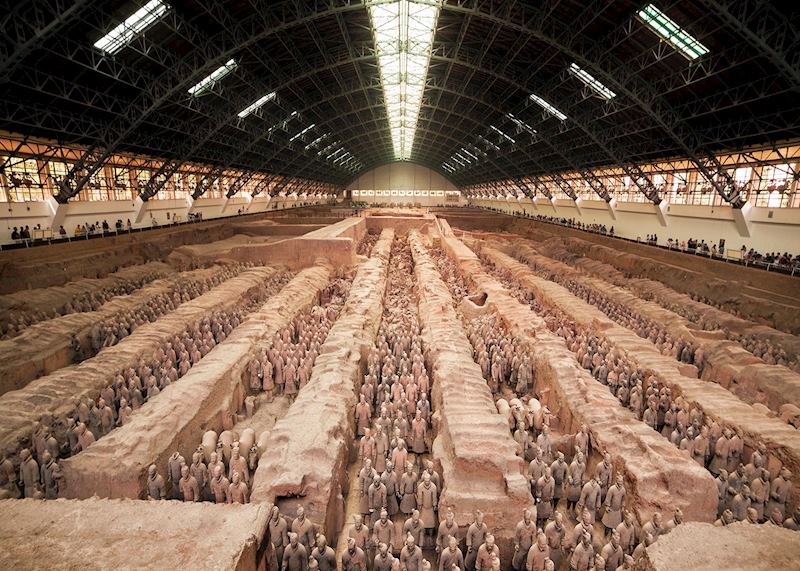

There’s a rush of noise, almost like the engine roar you hear on board a plane, as you step into the cavernous space of Pit One. And, appropriately enough, you’re standing in something more akin to an aircraft hangar than an exhibition hall. Your gaze tilts downward to the floor of the pit, and hones in immediately on row after row after row of austere, erect brown clay figures, staring intently ahead, battle-ready.

The size of grown men, their hands are curled around thin air, the halberd, spears and other arms they originally held having long since rusted away.

On a sweeping first glance, you might think that the warriors are carbon copies of each other. But look closer, and you’ll see subtle and not-so-subtle differences. After the initial impact of seeing the army face-on, my advice is to move to the sides of this vast room (where you won’t have to jostle the crowds for space) and spend several minutes studying a group of five or six warriors in detail.

What you don’t always get from pictures is how the warriors were purposely arranged to stand in imperial battle formation. There’s a vanguard of archers, flankers at the sides, charioteers in the middle (their wooden chariots are long gone, but their muscle-bound horses still accompany them) and a rearguard.

Different ranks and roles have different breastplates, hairstyles, and tunics. Some figures stand there like decapitated ghouls, their heads never located.

My guide, Leo, pointed out how the facial expressions of each warrior differ: some look solemn, some bellicose, some almost philosophical. A few seem to be breaking into a sly smile. Their physiques differ, too: some are stolid and barrel-chested, others slim and sinewy.

‘You know,’ said Leo, grinning shyly, ‘men from round here — people like me, whose families are from Xian — sometimes look at certain warriors and see our own faces reflected back at us. We think: hey, there’s my ancestor.’

You could spend hours in Pit One alone, but don’t miss (as many do) the ‘warrior hospital’ right at the rear. Here, you’re given a thrilling reminder that you’re visiting an active archaeological site, and you can witness the painstaking restoration work that’s still going on. Figures found broken into jigsaw-like fragments must be reassembled piece by piece.

Pits Two and Three

You can trust your guide to choose the quietest route for you around the complex. To that end, it can be a good idea to visit Pit Three before Pit Two. Although much smaller in size than Pits One and Two, Pit Three is like the Pentagon of the Terracotta Army. Here, you can get a good look at several immaculately restored generals in all their battle regalia (note their more elaborate double-knotted hairstyle, too).

A picture on the wall near Pit Three (easily missed) shows how the warriors were brightly painted until 32 seconds after they were unearthed, when the shades disappeared due to oxidation.

Like Pit Three, Pit Two is located in a large, darkened room. The pit itself is a mass of collapsed and petrified wooden beams, with broken figures and horses scattered pell-mell; it looks like they’ve just been brutally decimated in battle. (It also gives you a greater appreciation of the feat of the restoration work to date, as all the standing warriors were discovered in this state).

The main attractions in the Pit Two section are the statues displayed in individual glass cases, including a kneeling archer and a sage-looking military tactician. These displays allow you to inspect the details of the craftsmanship: you can see the ripple of muscle on the archer’s shoulder, and the tread on the sole of his boots.

Qin Shi Huang Emperor Tomb Artefact Exhibition Hall

This darkened hall, separate to the main pits, displays some bronze chariots, horses and a sedan chair found 20 m (66 ft) west of the emperor’s tomb.

Although the metalwork is impressive (the horses, for example, wear delicate head ornaments), this room is often cramped and incredibly crowded. Unless you have a real interest in seeing these items, I suggest just passing through and having a peek. Better to reserve the lion’s share of your time for Pit One — and guides usually allow time for a second visit to this most imposing of pits before you leave the complex altogether.

Best time of day to visit the Terracotta Army

The truth is there will always be crowds when you visit the Terracotta Army. Chinese domestic tourism is booming and, understandably, the warriors are a prime attraction. If you can handle an early start, the best time to visit is when the museum opens at 8.30am.

Most visits last around two hours. Crowds swell as the day wears on, though, and you might still share your visit with several tour groups despite an early start. My advice is to be stoical about it all. This does mean accepting that, at some point, you might well be elbowed out of the way by someone brandishing a selfie stick and a smartphone.

Guides will help you get to the quieter spots and find you the best vantage points over the pits. On a private tour, you’ll find it much easier to weave your way through the big tour groups and the complex as a whole.

Where to stay in Xian

The museum housing the Terracotta Army is located right on the outskirts of Xian, and there’s little of interest in the immediate vicinity. I’d opt to stay at the Sofitel inside Xian’s old city walls — not only will you have access to some of the best restaurants, but you’ll be able to walk the city walls easily, as well as the night market in the Muslim Quarter.

What is the Terracotta Army?

The 8,000-odd warriors and horses were made out of fired clay and construction started in 246 BC.

The figures were found close to the site of Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum, now a forested hump rising from the plains outside Xi’an. You might just glimpse it in the distance on your way to view the warriors in their purpose-built museum.

There’s a grisly backstory to their existence: before Qin Shi Huang, combatants would be buried alive alongside their leader on his decease. Seeing this as a waste of human resources, Emperor Qin decided to engage a huge taskforce in creating sculptures modeled precisely on his own imperial army.

Reputed to be a tyrant in life (despite his considerable achievements, such as standardizing Chinese writing), one theory goes that he desired an army to defend him in death.

Read more about trips to China

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in China