By Audley Colombia specialist Tomas

Colombia encompasses coffee-growing highlands, forward-thinking cities, wild coastal national parks, and immaculately preserved Spanish colonial towns where home-grown traditions are still going strong.

I love this diversity, and the fact you can see so much within a two-week trip — I always feel that Colombia is a country that’s more than the sum of its parts. It’s also a year-round destination. But there’s an even more pressing reason to go: to challenge the way Colombia is often still portrayed by the Western media.

Is it safe to visit Colombia?

The guerrilla- and drug-cartel-fuelled violence of the 70s, 80s, and 90s has given rise to the impression that today’s Colombia is still a dangerous, lawless place. While Colombia’s problems haven’t entirely been eradicated, they’re far removed from the places and cities I’m going to talk about.

The country has really opened up to the international travel industry over the past decade or so, and it’s firmly looking to the future. This is perhaps most exemplified by the city of Medellín (see below).

What to do in Colombia: my selected highlights

µþ´Ç²µ´Ç³Ùá

I admit I didn’t have massively high expectations of Colombia’s sprawling, flat capital, which is hemmed in by the peaks of the Andes’ Cordillera Oriental. I assumed it would be an impersonal, high-rise business district of a city, and you’d do little more than fly in and out.

But Bogotá does have two or three characterful elements. And while the glossy glass tower blocks exist, they sit alongside a historic core that radiates out from Plaza Simón Bolivar in a winding ribbon of churches and government palaces.

This old town, known as La Candelaría, is one of the best places to see the city’s celebrated (and now more or less legally sanctioned) street art. You’ll see all kinds of murals, portraits, and stencil work just by walking around, and, with this transient art form, there’s really no telling what you might find.

A guide helps when it comes to untangling the graffiti artists’ tags and subtle (or not so subtle) political connotations. My guide gave me a potted history of the deep-seated divisions between the country’s Liberal and Conservative factions, a schism that is closing today but which often plays out on the city’s underpasses and warrens of backstreets.

I was struck by the beauty of one piece in particular, which depicted the face of an indigenous person. Emanating from her hair were corn kernels, a traditional Colombian food source, and a hummingbird, a national symbol.

I’d also recommend setting aside an hour or two to explore the Museo del Oro (Gold Museum), a three-story El Dorado of more than 35,000 pre-Columbian gold items made by the country’s indigenous peoples. The finds displayed come from all over Colombia, from the southern border with Ecuador to the northern Caribbean shores.

In one darkened circular room, the Sala de Ofrenda, the relics are displayed all around the perimeter: lighting artfully illuminates different glinting objects in turn. Some of the pieces are minute hair or body decorations used by Colombia’s coastal Kogi people. Others are offerings that the indigenous Muisca people would cast into lakes to placate their gods.

The Paloquemao Market is located in a shabbier, more workaday area of the city, but it’s an excellent place to experience a slice of real Bogotano life. This unpretentious food market sells all kinds of fish, vegetables, meat, and flowers, but you’re really here for the pyramids of home-grown exotic fruits, which you can sample fresh from the stalls or have blended into smoothies and juices.

A guide is essential to help you identify the choice pickings, but you’ll mostly be surrounded by locals bartering for produce; you’re unlikely to see many other foreign visitors. Try the lulo, a ball-like fruit in a shade of atomic tangerine that’s so pungently citrusy it’s best consumed in juice form, or the guanabana, which looks like the spiky egg of an ostrich. The taste of its soft pulp is not dissimilar to South American chirimoyas (custard apples). Then there’s granadilla. Like an orange-skinned passion fruit, it bulges with black seeds encased in a squidgy, filmy sac. Use your teeth to bite through and then suck out the seeds and the succulent, lime-tanged flesh surrounding them.

Villa de Leyva

As you drive out of the capital, you soon move into a landscape of lakes and green hills scattered with identikit campesino smallholdings: a small building, a handful of crops, some tethered livestock. Sheep idle about on grassy banks in the middle of the road, impervious to traffic. I certainly didn’t expect such bucolic scenery so close to a city.

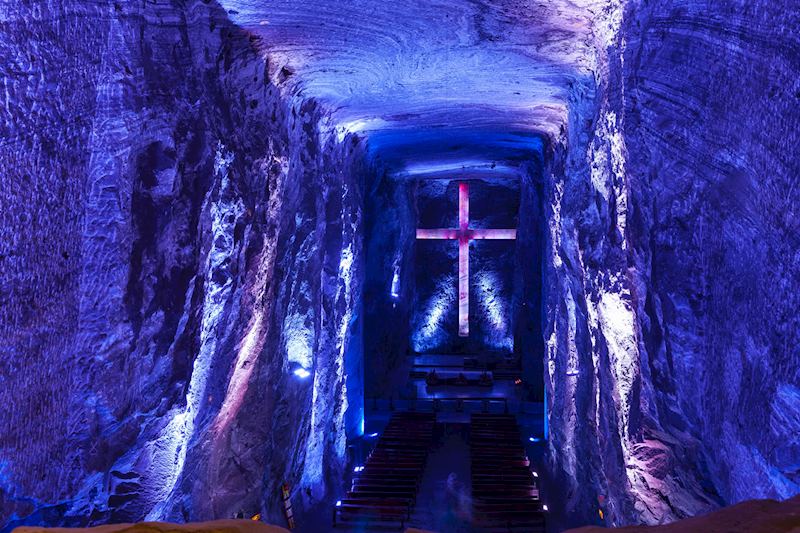

It’s a three-hour drive to Villa de Leyva, a whitewashed Spanish colonial town that offers a real change of pace from µþ´Ç²µ´Ç³Ùá. En route, I suggest stopping off for a leg stretch at the salt ‘cathedral’ (really a working church) of Zipaquirá.

Carved in an underground salt mine by God-fearing workers who wanted a place to worship, it’s a curious set of chambers designed around the 14 Stations of the Cross, each illuminated in a rainbow wash of light. At the end of the main nave, in the apse, a huge illuminated cross hangs suspended. My guide asked me how much I thought it weighed, before revealing that the cross is actually an illusionary shape carved into the halite rock.

Villa de Leyva itself has the feel of a time warp about it — in 1954 it was declared a national monument and its architecture has remained unchanged since then. A drowsy, quiet town with a clutch of cobbled streets and some excellently preserved 16th- and 17th-century churches, it does rouse itself into life in the evenings which are best spent nursing a drink at a café on the vast central plaza — the largest cobbled square in Latin America.

It’s also a good place to try your hand at traditional artisanal crafts. I had a go at weaving on a backstrap loom in a tiny place just off one of the cobbled old-town streets, and saw how hats, gloves, and ruanas (similar to ponchos) were painstakingly hand-made.

After a few hours’ hard graft, I came to the conclusion that the woven garments being sold in the town’s shops suddenly seemed very reasonably priced indeed.

Villa de Leyva also acts as a launch pad for various activities and experiences that may sound touristy but actually give you an even better taste of everyday Colombian life. I spent an afternoon playing the national sport (and, no, it’s not football (soccer)). Tejo involves throwing clay disks into a pit and trying to score points by hitting various small triangles loaded with (tiny, tiny) explosives. I played on a court, but the game is typically enjoyed at local watering holes. A little more extreme than backgammon or pool, perhaps.

The Zona Cafetera, or coffee region

I thought the hills around Villa de Leyva were green, and then I came to the coffee region (it’s only an hour’s flight from Bogotá to Pereira, the gateway town). The hillsides of this high-altitude, cool-climate zone are like a ragged, emerald-bright quilt of dense vegetation, frothy coffee plants, and fields of sugar cane, oranges, avocados, and cacao.

The high point of this region for me is the Cocora Valley, where you can take guided hikes to vantage points and see up close the area’s distinctive wax palms. They grow up to 200 m (656 ft) high and are a type of grass, not strictly a tree. Viewed from afar, their scale is deceptive. Stepping over a felled wax palm is like tiptoeing around a broken ship’s mast.

Paths are mostly unmarked, so you’ll need a good guide. You’ll also have to negotiate a few horses at pasture and grazing cattle. Keep your eyes peeled for hummingbirds.

Hikes easily combine with visits to the towns of Salento and Filandia to see the kaleidoscopic façades of the town’s houses. There’s a story behind them: during the dreadful period known as La Violencia in the 40s and 50s, Liberals would paint their houses red, while Conservatives’ homes were blue. Eventually, such divisions were wiped out by repainting the houses in all the shades of the spectrum.

I also suggest visiting a working finca (coffee farm), where you can get a holistic overview of the coffee-making process. I toured around a finca called San Alberto, observing how the beans were organically grown, selected and ground on site, then packaged in hessian bags. At the end, I took part in an aroma and taste test. Now, I’m not a big coffee drinker, but the end result was still surprising — sweet, mild, and smooth, with no hint of bitterness. It was a million miles away, taste-wise, from the instant blends.

In and around ²Ñ±ð»å±ð±ô±ôòÔ

I urge you to visit this place as it encapsulates just how much the country has progressed. Once the infamous stronghold of drug kingpin Pablo Escobar, the city is well and truly shrugging off its tainted reputation and has transformed itself into a rejuvenated mountain metropolis.

It not only experiments with daringly contemporary civic architecture (witness the blocky monolith of the Spanish Library or the botanical garden’s Orquideorama, a canopy of meshed ‘flower-trees’ similar to Singapore’s ‘supertrees’).

It has also made efforts to incorporate the poorer hillside slums (called barrios or comunas) into the wider city (and so break the cycle of drug cartel recruitment) through building outdoor escalators and funiculars to link up communities. I spent a morning in Comuna 13, seeing first-hand how its young people are taking part in street-art projects, learning breakdancing, and even recording reggaeton in a local studio.

Another way to experience Medellín is simply to wander around. There’s a particularly pleasant square, Plaza Botero, that local artist Fernando Botero has adorned with his characteristic sculptures of oversized — sometimes saucily voluptuous — bronze figures. The gentrified district of El Poblado is also an energy-filled, upbeat area with some good bars and restaurants.

Within a couple of hours’ drive from the city lie a couple of eccentric spots that are worth visiting. The first is a huge natural rock, a 198 m (650 ft) inselberg named El Peñol. If you scale its switchbacks of 740 steps, you’re rewarded with expansive views over a flooded valley.

What tickled me was the story behind this staircase to nowhere: it was, I learned, all the work of an enterprising local farmer. He then created an area for accompanying cafés and souvenir shops, and began charging an entrance fee. He’s now a local legend for dreaming up this business opportunity, and his statue greets you by the entrance gate.

East of the city, you’ll find the town of Guatapé. It seems unassuming enough until you see its vibrantly painted houses whose zócalos (bas-reliefs) are decorated with motifs representing the owner’s occupation or interests. One street is seemingly dedicated to history enthusiasts, while other houses display farming designs or musical instrument carvings.

Tayrona National Natural Park

Tayrona lies on Colombia’s north Caribbean coast, a 45-minute drive from the town of Santa Marta (itself a short flight from Bogotá or a four-hour drive from Cartagena). But dispel all images of languorous beach vistas from your mind. For a start, the snowcaps of the Sierra Nevadas are fewer than 48 km (30 miles) away to the south.

This isn’t a place for ‘flopping and dropping’. The sea is cerulean blue, and there are a couple of languid lagoons. But it’s mostly rampant wilderness, with windswept beaches scourged by riptides and littered with huge boulders, and thickets of jungle alive with red howler and capuchin monkeys.

You can trek to a couple of beaches, La Piscina and Cabo San Juan de Guia, where the water is slightly calmer and safe for swimming. En route, your guide will be able to tell you about the indigenous Kogi people, who not only own this parkland but consider themselves its guardians and the ‘elder brothers of the world’. Every year, they close a part of the park to help with its rejuvenation and maintain its ecological purity.

Cartagena

The most overtly historic and Spanish colonial of Colombia’s cities, the fortified port city of Cartagena has become something of a magnet for cruise ships. But while it’s getting busier, it’s still worth a day or two’s exploration.

The major coup is the well-preserved ramparts and defense structures encircling the historic old town, built by Spanish conquistadors to safeguard their New World gold from opportunistic pirates, privateers, and French corsairs. Buccaneer Sir Henry Morgan was even employed by the British crown to ransack the city, and the Spanish Inquisition once prowled its streets.

Now it’s a leisurely place peppered with boutique hotels and restaurants, and typically gilded colonial relics such as the Cathedral of Saint Catherine of Alexandria. Other than sauntering around the city walls (locals like to do it in the late afternoon, a tradition called ‘paseo’), I recommend settling yourself into Plaza de Bolivar between 5pm and 10pm to watch members of the city’s predominantly Afro-Colombian community dance cumbia. Here, the dance style competes with salsa, and was based on ritual courtship dances between former slaves.

Isla Múcura

If you’re looking for relaxation at the end of a trip, travel to the San Bernardo Archipelago in the Caribbean Sea, a two-hour boat trip from Cartagena (eschew the better-known Rosario Islands — they tend to get very busy with day-trippers). More specifically, head to Isla Múcura, a small coral island shrouded in palm forest that’s home to a single hotel, Punta Faro. The hotel, in fact, occupies the entire island.

Powdery sand, and the clearest seas I’ve ever seen (you don’t always need to snorkel to observe the tropical fish) have made this my first-choice beach escape in Colombia. Walking and cycling trails wind around the island, and dinner is a peripatetic affair, served at different spots each night.

As is often the case in Colombia, there’s a story behind Punta Faro’s existence — it was built to provide employment to the inhabitants of the nearby Santa Cruz del Islote. With a population of 1,247, despite being the size of two soccer pitches, it’s the most densely populated island on Earth.

- Read more about staying on Isla Múcura

Start planning your trip to Colombia

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in Colombia