By Italy specialist Laura

Well-placed for trade, Sicily has long been the crossroads of the Mediterranean. Merchants, invaders and immigrants have flocked to the island, first the Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans in ancient times, then Byzantines, Arabs and Vikings, followed by Normans, Germans and Spaniards. Their diverse influences are still seen in the souq-like markets, Norman churches graced with Byzantine domes, and the occasional Arabic word in the local language.

It’s no wonder so many have come and stayed — the island is a tempting jewel. The hills support venerable groves of olives, almonds, pistachios, oranges and lemons. The white pebbly beaches curve around aquamarine water. Above it all looms fiery Mount Etna, which gives the island its fertile soil.

- What to see in Sicily

- Sicily’s Greek and Roman sights

- Sicily’s hidden highlights

- What to eat in Sicily

- Where to stay in Sicily

- Best time to visit Sicily

- Getting to and around Sicily

What to see in Sicily

Palermo

Some street signs in Palermo are written in Italian, Arabic and Hebrew. The signs — not just in three languages but in three totally different alphabets — are a small but visceral reminder of the city’s multilayered cultural heritage.

In the city’s many open-air markets, narrow cobbled streets are lined with closely packed booths and shaded by a bright patchwork of tarps. The stalls are heaped high with fruits, seafood, herbs, honey and more. The feel of the market is a remnant of Arab rule in the 9th century and the loud, bustling scene hasn’t changed much over a thousand years.

The markets are also where you can try some of the local delicacies — granita (shaved ice typically sweetened with fruit syrup or infused with coffee), arancini (rice balls), panelle (fried chickpea fritters), and thick-crust Sicilian pizza. If you’re braver than I am, you might want to try stigghiola, a skewer of seasoned intestines cooked on a hot grill. In fact, many of the street food stalls display an assortment of raw food and you simply make your selection and watch it grilled right in front of you.

Taormina and Mount Etna

Perched on a hill, Taormina is a pretty little seaside town full of shops and cafés. It has been a popular retreat since the Victorian era and past visitors include Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, D.H. Lawrence, Tennessee Williams, and Truman Capote.

They all came to Taormina for its sweeping views down to the coastline and across to Mount Etna. The Ionian Sea ranges from deep blue to turquoise to aquamarine and the water is startlingly clear. The nearest beach, Isola Bella, is just a 10-minute cable car ride from town. It lives up to the second half of its name — bella means beautiful — but the pebbled beach is often crowded.

The city is also home to the Teatro Greco, a Roman amphitheatre thought to be built on the remains of an older Greek theatre. The concentric rings of seats look down onto a stage that seems suspended between sea and sky and Mount Etna looms on the southern horizon.

Taormina is also a convenient base for exploring Mount Etna, known to locals as ‘Mama Etna’. They’re fond of the stratovolcano even though there are major eruptions every few decades and smaller grumblings continue on a near-weekly basis. That’s because the outpourings of ash and lava have blessed the island with rich, volcanic soil.

I took a 4x4 tour of the volcano, which is the largest in Europe. The landscape is surreal, consisting of lunar hills of gravelled grey ash. My guide pointed out each lava flow as we passed it and told us the date of the eruption that had caused it. It was a reminder of how Mama Etna continues to affect the daily lives of Sicilians. Another reminder came when my guide checked in with the local volcanologists before we started the tour. The scientists set a maximum height on the volcano’s slope for the tours each day, to ensure visitors’ safety.

Western Sicily

On a mountain near the island’s western coast, Erice is a medieval walled city that sits at a dizzying height of 750 m (2,460 ft) above sea level, and offers sweeping views of the Tyrrhenian Sea and the white buildings in the towns below.

Erice has a long tradition of producing dolci (sweets) that take advantage of the almonds and oranges introduced by the Arabs in the 9th century and the cocoa beans introduced by the Spanish in the 16th century. Look for pasticceria on the sign to find the shops that sell the treats, which include sculpted marzipan candies. One emporium belongs to Maria Grammatico, a fierce octogenarian whose challenging life has been documented in the book Bitter Almonds.

Caught between Mount Erice and the sea is the small town of Trapani. Densely built on a spit of land on the western tip of the island, Trapani was the heart of a complex trade network during the Crusades. Today, it’s known for its salt flats — long, narrow channels filled with briny Mediterranean water in the spring and left to evaporate in the summer months. The process hasn’t changed much over the centuries, powered by wind, waves, sun and strong men who shovel the crystals into piles that glitter whitely in the heat.

Modica, Ragusa and Noto

In 1693, the strongest earthquake in Italian history destroyed much of Sicily’s southeast. The three small towns of Modica, Ragusa and Noto were rebuilt in a short-lived but distinctive style known as Sicilian Baroque.

During this time, the usual Baroque embellishments were given even more flamboyant flourishes, with the addition of grinning masks, elaborate balconies and external staircases, belfries, and inlaid marble mosaics. The towns are set in the gentle hills and sharp valleys of the Hyblaean Mountains, and you can spend a whole day exploring their narrow streets, showy palazzi and extravagant churches.

In Modica, chocolate is a local delicacy. Cioccolato di Modica is acknowledged and protected by the Italian government and labelled as PAT (prodotto agroalimentare tradizionale). Derived from original Aztec xocoatl, this chocolate boasts a distinctly gritty texture and is usually very intense, with little to no sugar. The confectioners do often add chillies, providing an unexpected kick.

Sicily’s Greek and Roman sites

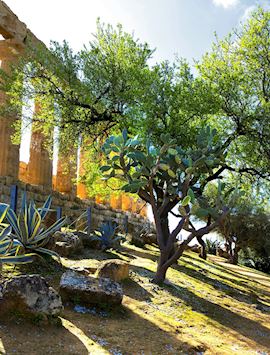

During my travels, I’ve been to countless classical ruins all over Italy, but visiting those in Sicily was a new kind of experience. In Agrigento, Segesta, Syracuse, and Taormina, many of the sites are Greek rather than Roman, thus older than the mainland’s ancient survivors, but that wasn’t the largest difference.

On Sicily, most of the ruins aren’t roped off at all, and you can simply stroll among them. In Segesta, I could have scooped up bits of broken pottery off the ground, and I watched a child clamber over a fallen marble column. The scale of the unexcavated, unprotected ruins is almost shocking.

There are some intact buildings, but don’t be fooled. These are Victorian reconstructions, reassembled from original stones during the vogue for the Grand Tour, when European aristocracy was fascinated with all things classical.

Both the unfettered access and the casual re-appropriation seemed to exemplify the attitude of the Sicilians toward their long history. I asked my guide, Lorenzo, if he was worried about the long-term effects of people manhandling the island’s cultural heritage. He shrugged and quoted me an old Sicilian saying, 'When you find the table laid for you, you eat!'

I asked him to elaborate and he told me that, while the sites are managed and protected, Sicilians have traditionally been practical and unsentimental. There’s no need to build a church from scratch when there’s a Greek temple already there. If a site is full of carved marble, locals would use it for a house. It drove home the idea that I was just the latest — and not the last — in a long line of people who have come to this ever-changing land.

Sicily’s hidden highlights

Comparatively, all of Sicily is a hidden gem, much less visited than much of the mainland. Rome, Florence or Venice can feel like visiting a museum but Sicily isn’t like that. It’s a living, changing island with a comfortably casual authenticity. This isn’t to say there aren’t a few off-the-beaten-track places.

Castelbuono

This small Sicilian town is best known for the eponymous castle, built by the powerful Ventimiglia family who ruled this area from the 14th to the 16th centuries. Many of the streets and buildings date to that era, creating a medieval feeling as you stroll through the narrow, cobbled lanes. The castle is interesting on its own, combing Norman-French, Arab, and German influences to create an imposing cube-like edifice.

But, in the end, I was most charmed by the people. My guide, Elizabeth, was a native and introduced me around as if I were a visiting friend. When my new acquaintances discovered I was an American, they insisted on introducing me to the only other American in town, a girl who’d married a Sicilian man and worked at the bakery. Everyone seemed determined to impress upon me how much they loved and admired their town. I left with a small bag of dolci and fond memories.

Zingaro Natural Reserve

Zingaro Natural Reserve, or la Riserva naturale orientata dello Zingaro, is located on the northwestern tip of Sicily and stretches along the Gulf of Castellammare’s coast. It’s criss-crossed with walking paths that take you up and down gentle hills through unspoiled landscapes.

When I visited recently, my guide and I seemed to have the whole area to ourselves, only occasionally seeing other visitors. As we walked, she told me the names of the plants and birds, as well as the history of the reserve, which only dates back to 1981. Strolling along deserted coves, I admired the Mediterranean blue of the water lapping up on the white stone beaches. It was a quiet respite from the hustle of Palermo and worth the trip.

What to eat in Sicily

Food is one of the reasons I visit Sicily. Thanks to its rich soil, the island produces an amazing variety of foods: almonds, pistachios, oranges, lemons, olives, apples, pears, cherries, figs, and plums, to name but a few. Many of the varieties are unique to the island and worth searching out at a local market. Fishermen catch a remarkable assortment of seafood in the local waters, all served fresh and often prepared with a nod to the island’s North African past.

Even the most popular of Sicily’s wines, like Marsala, aren’t as well-known as those from the mainland, but the island produces exceptional vintages on the slopes of Mount Etna. Many of them are protected by the government with DOCG or DOC designations, labels that indicate that the wine adheres to strict regulations. The volcano’s varied microclimates produce very different wines depending on the vineyard’s location, and often the production runs are so small there aren’t enough bottles to export.

Where to stay in Sicily

In east-coast Taormina, the Belmond Villa Sant'Andrea is a graceful seaside hotel that combines grand elegance with a relaxed Mediterranean feel. Set in an 1830s villa, it takes full advantage of its private beach with alfresco dining and spa options and ocean-view rooms. A cable car can whisk guests straight to the heart of the town.

A little farther south, the Monaci delle Terre Nere offers a totally different experience. The rooms are scattered among the grounds of an old estate, set in the old barn and other outbuildings. The hotel embraces the ideals of the Slow Food movement and produces much of its own comestibles on site, including a wine made from carricante, a grape variety found only in the Etna region.

Best time to visit Sicily

When you visit Sicily depends on what you want to do there. I find July and August are very hot and crowded with visitors who come for the beaches, so suggest avoiding those months. If you want to explore the cities and towns, plan your visit before or after the heat.

I like visiting between April and June, when the island blossoms with spring flowers and the markets overflow with seasonal produce, including wild artichokes and fresh fava beans. As with everywhere in Italy, Easter is an important festival and Settimana Santa (Holy Week) can be crowded as people gather for the processions. But the rest of the season is much quieter than the busy summer months and the weather is ideal for touring towns.

Summer crowds thin out from late September, yet the weather remains pleasant through November. Hardy souls can even swim in the autumn months (though the warm-blooded locals will shake their heads).

Christmas is a busy time here and across the country. After that, though, the island empties out, despite mild temperatures and mostly sunny skies on the coast. Bear in mind that the interior gets snow, rain and wind. I find it’s an excellent time to travel if you want to stick to the coastal cities but avoid crowds entirely — prices are also much lower.

Getting to and around Sicily

With four international airports and two domestic airports, it’s easy to reach Sicily whether you’re flying in from another country or from a different part of Italy. Once there, you’ll find most of the towns and cities are compact enough for walking and taxis are plentiful. For visits to sights outside of towns or to travel between them, we can arrange for private transfers.

If you prefer to drive yourself, we can arrange for a car and provide detailed directions. Licensed UK and EU drivers are able to drive here, though US and Canadian drivers will need an International Driving Permit (IDP), which you must keep with you when you’re in the car.

Start planning your trip to Sicily

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in Italy